Beyond Westphalia: The Ummah, Pluriversalism, and a New Global Imaginary

Introduction: The Westphalian World and Its Discontents

The modern world order is anchored by the presumption that the Westphalian system of sovereign nation-states represents the natural, inevitable, and universally applicable framework for global governance. This model, often traced to the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, is celebrated for championing principles such as territoriality, exclusive state sovereignty, and the doctrine of non-interference in the domestic affairs of other states.1 This foundational structure is formally enshrined in key documents of international law, including the United Nations Charter, which explicitly forbids intervention in matters of a state’s domestic jurisdiction.1 However, the intellectual and practical foundations of this system are now under unprecedented strain. The trans-boundary crises of the 21st century—from the existential threat of climate change to the entrenching of systemic poverty and the persistence of intractable conflicts—demonstrate a profound mismatch between a 17th-century European paradigm and a hyper-interconnected global reality.4

This article deconstructs the intellectual and historical mythos surrounding the Westphalian model, arguing that its continued dominance is less a testament to its efficacy and more a consequence of its powerful, yet fragile, ideological and historical construction. It contends that the state-centric level of analysis, which has long dominated the field of International Relations, is intellectually and ontologically insufficient for comprehending and addressing contemporary global challenges. In its place, this report will explore the growing relevance of a pluriversal approach, one that recognizes a "world of many worlds," each with its own valid and historically-rooted framework for order and coexistence.6 Specifically, it will analyze two compelling civilizational frameworks—the Islamic concept of the Ummah and the Chinese idea of Tianxia—as potent and ethical alternatives. The analysis will demonstrate that the Ummah, in particular, offers a robust and compelling imaginary for a new global order founded not on competitive self-interest but on principles of justice, peace, and shared prosperity.9

Deconstructing the Westphalian Myth: A Genealogy of a Fabricated Order

The conventional wisdom in textbooks of international relations and international law holds that the Peace of Westphalia in 1648 marked the birth of the modern international system.11 This narrative, which has held the status of "textbook knowledge," posits that the treaties replaced a universalistic, hierarchical order dominated by the Holy Roman Empire and the Pope with a new system of independent and sovereign states.1 A closer look at the historical record, however, reveals this story to be a powerful and deliberate intellectual fabrication.13

Historical scrutiny and textual analysis show that the Peace of Westphalia, which was comprised of two distinct treaties, was a pragmatic resolution to the complex constitutional and religious conflicts of the Thirty Years' War.12 It did not establish the modern, exclusive form of sovereignty but rather strengthened a system of jurisdictional arrangements that were already in place.13 The concepts most closely associated with the Westphalian system—such as the principle of non-interference in domestic affairs and the idea of the "nation-state" as a fusion of a single ethnic group and a sovereign territory—were not developed until the 18th and 19th centuries, respectively.1 The modern international system, with its emphasis on sovereign equality, only reached its "peak in the 19th and 20th centuries".1 This historical de-centering suggests that the 1648 treaties were not the origin point of a new order but merely one step in a much longer and more complicated evolution.12

The perpetuation of this "Westphalian myth" is not a benign historical mistake but a foundational ideological project. From a post-structuralist perspective, the discipline of international relations has been shaped by a "dominant discourse" that frames its core concepts—like sovereignty and security—in an inherently Eurocentric way.16 This approach argues that what is accepted as "knowledge" is not objective but is "produced rather than discovered" and is often a reflection of the interests of powerful, elite actors.16 The Westphalian myth serves as a "regime of truth" that presents the rise of the European state system as a "linear, inevitable, and laudable process," thereby granting it an unassailable sense of legitimacy.13

The purpose of this fabricated history is to create a powerful binary opposition, one that positions the "civilized" West as the sole progenitor of a rational and modern world order.18 This process of exclusion transforms what is merely "cultural difference" into "legal difference," deeming non-Western political thought and governance models "unfit for full sovereignty".18 By presenting its own historical trajectory as the universal standard, this discourse systematically excludes alternative political epistemologies and justifies a global hierarchy. Critics of post-Westphalian policies, such as humanitarian intervention, argue that such actions are nothing more than a continuation of "Euro-American colonialism" under a new guise, a powerful demonstration of how this historical narrative continues to serve as a justification for neocolonialism and the subjugation of non-Western agency.1

The Crises of a State-Centric World: The Myth of Control Collapses

The intellectual and historical fragility of the Westphalian system is now matched by its demonstrable inability to contend with the crises of the 21st century. The model’s fundamental premise of a "fixed and unchanging" physical geography is rendered obsolete by the trans-boundary nature of climate change.4 Climate events, such as extreme heat waves and rising sea levels, do not respect the "confines of established national boundaries" and thus expose a "fundamental tension between sovereignty and climate change".4 The Montevideo Convention's pillars of sovereignty—a fixed territory, a permanent population, and clearly defined maritime boundaries—are all directly undermined by a fluid and shifting planetary environment.4 As coastlines recede and low-lying island nations face submersion, the very territorial basis of statehood is jeopardized.4 Furthermore, the climate displacement of entire populations challenges the presumption of a "permanent population," raising complex questions about the future of sovereignty and citizenship in a world of climate refugees.4

The challenges posed by neoliberal globalization are equally acute, further exposing the obsolescence of the Westphalian framework. The rise of a globalized economy, characterized by the "stateless corporation" and the free flow of capital, has dramatically reduced the capacity of states to control their own economic and social processes.21 The traditional "law of one price" has created new inequalities, concentrating wealth in the hands of a few privileged sectors while worsening the conditions of the disadvantaged.22 In a globalized world, a state's ability to act as the primary, self-contained locus of power has been "undoubtedly in decline".23

A particularly potent aspect of this erosion is the instrumentalization of sovereignty itself. As global financial and economic systems weaken the state’s capacity to govern effectively, proposals such as the "Responsibility to Protect" (R2P) emerge, arguing that a state’s sovereignty is conditional upon its ability to protect its citizens from mass atrocities.24 This creates a powerful and troubling paradox. On one hand, neoliberal globalization limits a state's economic autonomy, making it more vulnerable to internal instability and conflict.5 On the other hand, a state's failure to maintain order—often as a direct result of these external economic pressures—is then used as a pretext for "humanitarian intervention" by the very international community that benefits from the neoliberal system.1 Critics argue that this process is less about protecting human rights and more about re-establishing a global hierarchy, justifying external intervention in the affairs of states that are not aligned with dominant interests.1 The R2P doctrine, in this view, is not a benevolent principle but a new form of "paternalism" that makes sovereignty conditional and, in doing so, erodes its moral and political significance, a process that neocolonial nationalists have long warned against.24

Toward a Pluriversal International Relations: A "World of Many Worlds"

In light of the profound intellectual and practical failures of the Westphalian model, a growing number of scholars and activists are advocating for a fundamental shift in the discipline of International Relations. Pluriversal International Relations (PIR) is an intellectual and political project that directly challenges the state-centric paradigms of realism and liberalism by rejecting their "homogenizing and universalised violence".7 It moves away from the "epistemologically individuating and atomizing lens" that views states as the exclusive and autonomous sites for analysis.6 Instead, PIR foregrounds the experiences and thought of the Global South, envisioning a "world of many worlds," each with its own valid and enduring cosmology.6 The goal is to "weave together diverse cosmologies and practices" and to recognize that modernity is not a single, linear process but a multiplicity of paths shaped by different cultural and historical trajectories.7

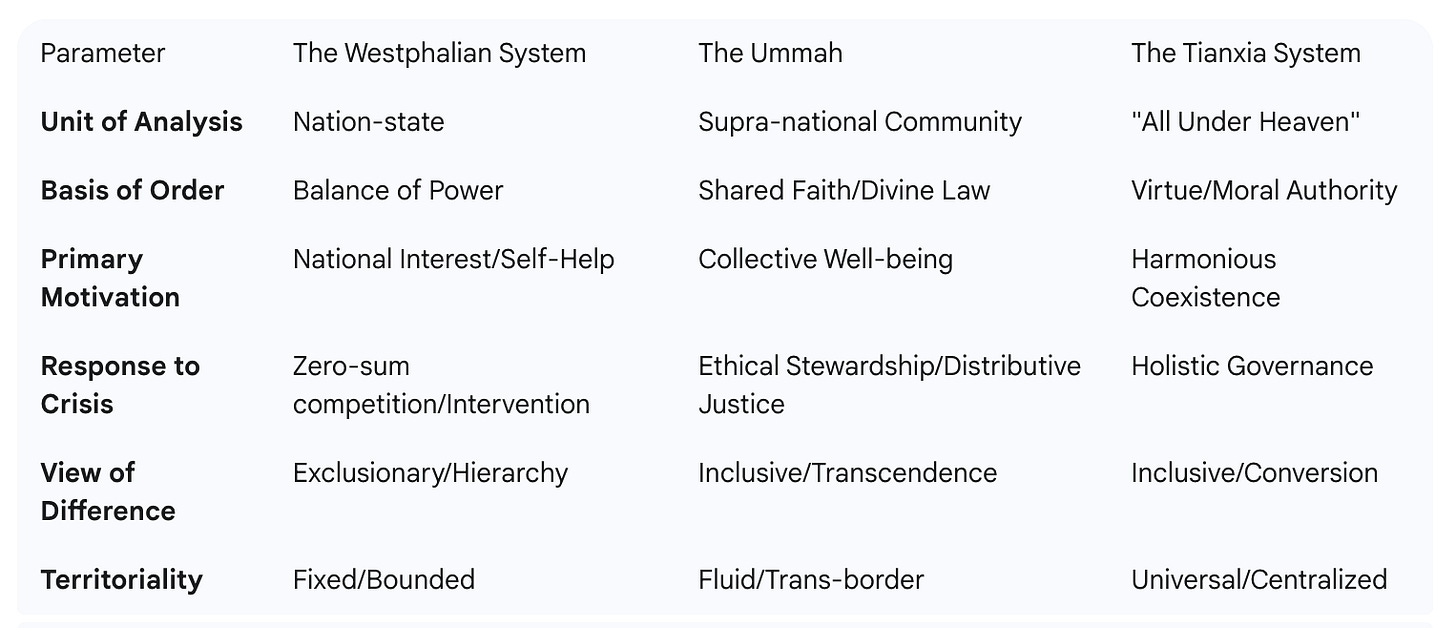

Within this pluriversal perspective, civilizational frameworks of order emerge as compelling alternatives to the nation-state. Two particularly powerful examples are the Islamic concept of the Ummah and the Chinese idea of Tianxia. Both systems predate the Westphalian order and offer a rejection of its core principles of exclusionary sovereignty and national interest.29 The Ummah, a community bound by shared faith that transcends ethnic and national divides, is a counter-hegemonic narrative that provides an alternative to the nation-state paradigm.29 The Tianxia system, or "all under Heaven," posits a holistic, ecological, and inclusive world order based on a moral authority rather than brute force.30

The fundamental differences between these two alternative frameworks highlight the pluralism of a post-Westphalian future. While both the Ummah and Tianxia reject the exclusionary logic of the nation-state, they do so from distinct philosophical foundations. Scholarly comparisons note that the Tianxia system is rooted in an "immanentist cosmological principle devoid of theological pretensions," where moral authority is derived from an internal, shared virtue.35 The Ummah, by contrast, is a community bound by a "vertical relation to the One," a transcendent and external source of law and morality.10 The Ummah is therefore a project of transcendence, while Tianxia is a project of immanence. This contrast reveals that a pluriversal world is not a monolithic utopia but a mosaic of diverse, and potentially conflicting, moral and cosmological projects. The central challenge for these and other civilizational models is how to reconcile inclusion with difference without reverting to historical patterns of "conquest and conversion".35

The table below provides a concise overview of the core philosophical and practical distinctions between the Westphalian system and these pluriversal alternatives.

The Ummah and Its Promise: A Framework for Justice, Peace, and Prosperity

The Islamic concept of the Ummah is a foundational element of Islamic political thought and consciousness, with over 64 references in the Qur'an.29 Historically, the Ummah emerged as a radical departure from the prevailing tribal and kinship-based social structures of 7th-century Arabia.33 The Constitution of Medina, an early blueprint for governance, explicitly declared that its members—including Muslims, Jews, and Christians—were to be considered "one ummah," united by a common social contract that transcended blood ties.33 This historical precedent demonstrates the concept's innate capacity for pluralism and inclusivity, a quality that directly contrasts with the nationalist, mono-ethnic logic of the nation-state model.15 In the modern era, the idea of a global Ummah has been revived as a "counter-hegemonic narrative," a response to the "lasting 'trauma'" of the abolition of the Ottoman Caliphate and the subsequent imposition of Westphalian borders on the Muslim world.29

The Ummah, as a re-imagined civilizational framework, offers a powerful alternative to the failures of the Westphalian system, particularly in the face of contemporary global crises.

Economic Justice and Distributive Ethics

While the Westphalian model is increasingly undermined by neoliberal globalization and its attendant inequalities, a global Ummah would be centered on principles of economic justice and shared responsibility.22 The Ummah-centered economy would emphasize "distributive justice, equitable resource allocation, and ethical consumption" as core principles.9 This is not an abstract ideal but is rooted in concrete Islamic principles, such as

zakat (obligatory alms-giving) and waqf (charitable endowments), which are designed to "eradicate poverty" and foster a social system that prioritizes human dignity over profit.9 The Ummah, in this sense, provides a systemic alternative to the "debt-based development and neoliberal austerity" that has plagued the developing world.9

Ecological Stewardship

The Westphalian system, with its emphasis on bounded territory and economic competition, has proven insufficient to address the trans-border crisis of climate change, a problem rooted in the "extractivist and exploitative practices of modern capitalism".4 By contrast, the Ummah’s framework is founded on the Qur'anic concept of humanity's role as

khalifa fi al-ard, or "stewards of the Earth".9 This is a profound ontological shift, moving from a view of humanity as a master of nature to that of a custodian of a divine trust. In this framework, environmental degradation is not merely a legal or economic problem but a profound moral and spiritual failing, an abdication of a divinely ordained responsibility.9 This ethical lens provides a powerful corrective to the limitations of the nation-state model, which lacks a compelling ethical basis for addressing a planetary crisis.4

Inclusive Governance

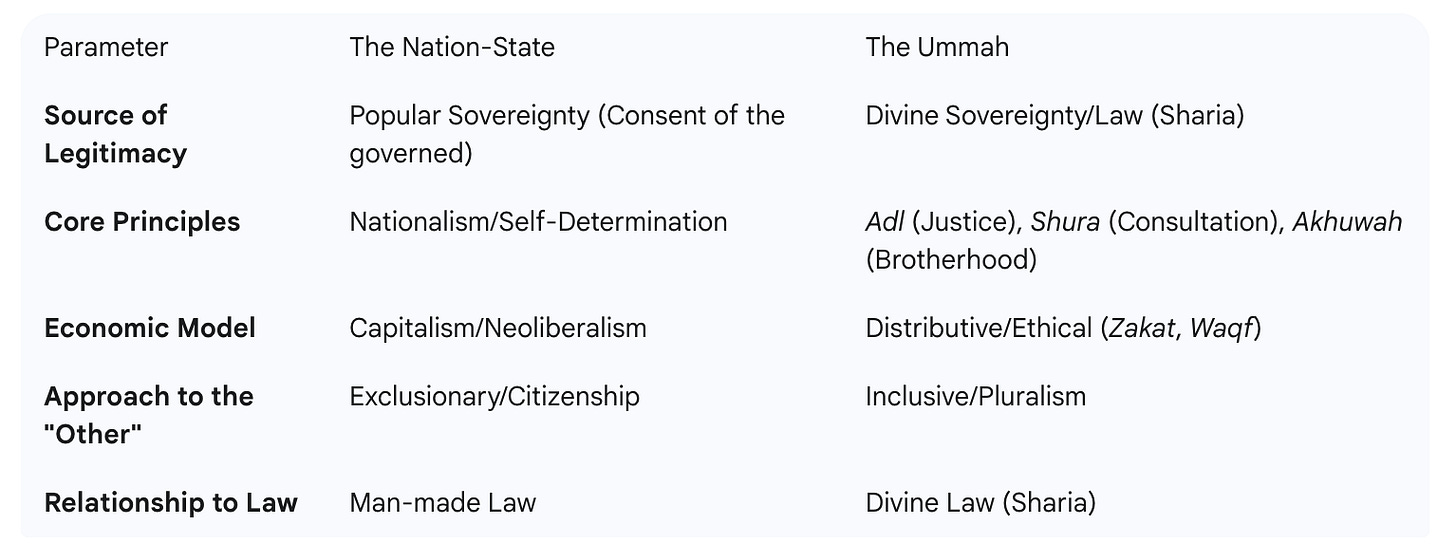

The Ummah is guided by core Islamic political principles that offer a stark contrast to the modern nation-state’s reliance on popular sovereignty and nationalism. The principles of Shura (consultation) and Adl (justice) are foundational to a governance model that prioritizes the views and well-being of the governed and ensures equity in resource allocation and the defense of individual rights.10 This is a move toward a form of "participatory governance" that aims to be both accountable and inclusive.10 The Ummah, as a pluralistic community, would be guided by the "Prophetic example of inclusivity," protecting the rights of all, including non-Muslims, and ensuring that "marginalized voices are heard and protected".9 This vision is a powerful antidote to the exclusionary citizenship regimes and ethnic conflicts that are so often a direct consequence of the nation-state model.15

The table below provides a more granular comparison of the governance principles of the Ummah and the nation-state, highlighting how the former provides a framework for addressing the very issues the latter has created.

Comparative Analysis and Future Directions

The intellectual project of moving beyond Westphalia is not exclusive to Islamic political thought. The Chinese concept of Tianxia, as a civilizational framework, offers a parallel critique of the nation-state while highlighting a distinct philosophical foundation. Scholars have noted that while the Ummah is a project of transcendence, the Tianxia system is an "immanentist cosmological principle" that is "devoid of theological pretensions".35 The Ummah’s universalism is rooted in a "vertical relation to the One," a transcendent source of truth and morality, while Tianxia’s is rooted in an immanent "All-under-Heaven," where peace and harmony are achieved through moral authority and virtue.30 The existence of both of these frameworks demonstrates that a pluriversal world is not a single, monolithic alternative but a complex mosaic of diverse and potentially conflicting projects.

The historical relationship between the Islamic and Chinese civilizations provides a tangible example of how these civilizational frameworks have coexisted and interacted. The Battle of Talas in 751 CE, where the forces of the Umayyad Caliphate defeated the Chinese Tang Dynasty, is often seen as a decisive moment that determined which of the two civilizations would predominate in Central Asia.37 Yet, this military encounter was followed by centuries of sustained interaction, leading to the flourishing of Muslim communities within China itself during the Song and Ming dynasties, with Muslims serving in high-ranking administrative and military posts.38 This history of both conflict and coexistence raises a fundamental question for a pluriversal future: How can these civilizational projects move beyond historical rivalries and engage in a dialogue that is not aimed at "conquest or conversion" but at mutual understanding and cooperation?35

Conclusion: A Glimpse into the Pluriverse

The Westphalian system, far from being the natural and inevitable order of the world, is an intellectual construct that is now intellectually and practically obsolete. Its core principles of fixed territoriality and exclusive sovereignty are collapsing under the weight of trans-boundary challenges like climate change and the pervasive inequalities of neoliberal globalization. The discipline of International Relations must move beyond its state-centric and Eurocentric foundations and embrace a pluriversal perspective that recognizes the validity and relevance of alternative civilizational frameworks.

The Islamic concept of the Ummah provides one such powerful and compelling alternative. It is not an exclusively Muslim project but a "universal ethic of care and justice" that transcends borders and prioritizes collective well-being, ecological stewardship, and distributive justice over the competitive individualism of the modern liberal order.9 The historical and philosophical encounter with a framework like the Chinese Tianxia further underscores that a post-Westphalian future is not a new singular order but a "world of many worlds" that must find a way to coexist.

This report, therefore, concludes by posing a series of questions that open the door to further inquiry and action. What are the practical and ethical challenges of institutionalizing the principles of shura and adl on a global scale? How can the global Muslim community overcome internal sectarian and national divides to actualize the vision of a unified Ummah? Finally, what are the mechanisms by which the Ummah and other civilizational projects might forge a new form of global order that moves beyond rivalry to one of mutual respect, and what new form of global law would be required to support such a pluriverse? These are not easy questions, but their contemplation is a necessary first step toward building a more just and sustainable world.

This article was written based on original concepts and structure by the author. Generative AI was used to assist with elaboration, refinement, and image.

Works cited

Westphalian system - Wikipedia, accessed August 21, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Westphalian_system

en.wikipedia.org, accessed August 21, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Westphalian_system#:~:text=The%20Westphalian%20system%2C%20also%20known,law%20teachings%20of%20Hugo%20Grotius.

Oxford Public International Law: Sovereignty, accessed August 21, 2025, https://opil.ouplaw.com/display/10.1093/law:epil/9780199231690/law-9780199231690-e1472

Reconsidering Sovereignty Amid the Climate Crisis | Carnegie ..., accessed August 21, 2025, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2025/03/reconsidering-sovereignty-amid-the-climate-crisis?lang=en

Kingsbury-Sovereignty-Inequality.pdf - Institute for International Law ..., accessed August 21, 2025, https://iilj.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Kingsbury-Sovereignty-Inequality.pdf

Coming soon: Pluriversal International Relations - Bristol University ..., accessed August 21, 2025, https://policy.bristoluniversitypress.co.uk/coming-soon-pluriversal-international-relations

Pluriversal International Relations - | IPSA, accessed August 21, 2025, https://www.ipsa.org/na/call-for-papers/pluriversal-international-relations

Do pluriversal arguments lead to a 'world of many worlds'? Beyond the confines of (anti-)modern certainties - The University of Manchester, accessed August 21, 2025, https://hummedia.manchester.ac.uk/institutes/gdi/publications/workingpapers/GDI/gdi-working-paper-202156-masaki.pdf?utm_content=buffera480d&utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter.com&utm_campaign=buffer

Toward a global umma. 19 December 2024 | by Dylan Evans | Medium, accessed August 21, 2025, https://medium.com/@evansd66/toward-a-global-umma-407e932c544c

Islamic Political Thought and Chinese Governance: A ... - Dialnet, accessed August 21, 2025, https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/9970565.pdf

www.byarcadia.org, accessed August 21, 2025, https://www.byarcadia.org/post/the-peace-of-westphalia-the-beginning-of-modern-international-relations#:~:text=The%20Treaty%20of%20Westphalia%20is,be%20found%20in%20this%20treaty.

The Westphalian myth and the idea of external sovereignty (Chapter 3), accessed August 21, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/sovereignty-in-fragments/westphalian-myth-and-the-idea-of-external-sovereignty/894BD9AF4AAA7112F870084F05AFC8C4

Beyond the Nation-State - Boston Review, accessed August 21, 2025, https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/beyond-the-nation-state/

The Peace of Westphalia | In Custodia Legis - Library of Congress Blogs, accessed August 21, 2025, https://blogs.loc.gov/law/2017/10/the-peace-of-westphalia/

Nation-state | Definition, Characteristics, & Politics - Britannica, accessed August 21, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/topic/nation-state

Introducing Poststructuralism in International Relations Theory, accessed August 21, 2025, https://www.e-ir.info/2018/02/13/introducing-poststructuralism-in-international-relations-theory/

Katy Gillespie: How does Poststructuralism unsettle traditional IR theoretical frameworks?, accessed August 21, 2025, https://3sjournal.com/katy-gillespie-how-does-poststructuralism-unsettle-traditional-ir-theoretical-frameworks/

Ben Haldane: The Eurocentric Foundations of International Relations Theory, and Why They Matter | The Student Strategy & Security Journal, accessed August 21, 2025, https://3sjournal.com/ben-haldane-the-eurocentric-foundations-of-international-relations-theory-and-why-they-matter/

The Obsolescence of the Westphalian Model and the Return to A ..., accessed August 21, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335870223_The_Obsolescence_of_the_Westphalian_Model_and_the_Return_to_A_Maximum_State_of_Exception

'Eurocentrism' in the Field of International Relations (IR) - Roads Initiative, accessed August 21, 2025, https://theroadsinitiative.org/eurocentrism-in-the-field-of-international-relations-ir/

Sovereignty - International Law, State Authority, Autonomy | Britannica, accessed August 21, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/topic/sovereignty/Sovereignty-and-international-law

Globalization And the Challenges to State Sovereignty and Security, accessed August 21, 2025, https://www.lebarmy.gov.lb/en/content/globalization-and-challenges-state-sovereignty-and-security

Globalization and the State: Assessing the Decline of the Westphalian State in a Globalizing World - Inquiries Journal, accessed August 21, 2025, http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/articles/1550/globalization-and-the-state-assessing-the-decline-of-the-westphalian-state-in-a-globalizing-world

The limits of sovereignty as responsibility - UC Berkeley Law, accessed August 21, 2025, https://www.law.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Rethinking-International-Responsibility.pdf

Globalization and the Crisis of Sovereignty, Legitimacy, and Democracy, accessed August 21, 2025, https://library.fes.de/libalt/journals/swetsfulltext/16126214.pdf

International relations theory - Wikipedia, accessed August 21, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_relations_theory

(PDF) Introduction to the Special Issue: Pluriversal relationality - ResearchGate, accessed August 21, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/364044275_Introduction_to_the_Special_Issue_Pluriversal_relationality

(PDF) A future for the theory of multiple modernities: Insights from ..., accessed August 21, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258190265_A_future_for_the_theory_of_multiple_modernities_Insights_from_the_new_modernization_theory

Re-Thinking The Politics Of The Umma (Muslim Bloc) : The Call for Islamic Global Politics, accessed August 21, 2025, https://trepo.tuni.fi/handle/10024/157623

Full article: 'Thinking through the world': a tianxia heuristic for higher education, accessed August 21, 2025, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14767724.2022.2098696

Tianxia - Wikipedia, accessed August 21, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tianxia

The Concept of Ummah: Unity, Significance, and Iqbal's Vision Islamic World View and Civilization - ResearchGate, accessed August 21, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/388490485_The_Concept_of_Ummah_Unity_Significance_and_Iqbal's_Vision_Islamic_World_View_and_Civilization

Ummah - Wikipedia, accessed August 21, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ummah

Rethinking Empire from a Chinese Concept 'All-under-Heaven' (Tian-xia) - ResearchGate, accessed August 21, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228916504_Rethinking_Empire_from_a_Chinese_Concept_'All-under-Heaven'_Tian-xia

Tianxia in Comparative Perspective: Alternative Models of Geopolitical Order - Freie Universität Berlin, accessed August 21, 2025, https://www.geisteswissenschaften.fu-berlin.de/v/dchan/veranstaltungen/Tianxia-Program.pdf

Challenges to State Sovereignty (1.2.4) | IB DP Global Politics HL Notes| TutorChase, accessed August 21, 2025, https://www.tutorchase.com/notes/ib/global-politics/1-2-4-challenges-to-state-sovereignty

The Battle between the Islamic Caliphate and China - Islam21c, accessed August 21, 2025, https://www.islam21c.com/politics/the-battle-between-the-islamic-caliphate-and-china/

History of Islam in China - Wikipedia, accessed August 21, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Islam_in_China